California’s Water Dilemma

Part 1: We Cannot Manage What We Don’t Measure

By Arian Aghajanzadeh

November 28, 2023

In discussions about California’s environmental challenges, the narrative often centers around the issue of water scarcity—a critical concern given the state’s climatic patterns and agricultural demands. However, a more pressing, yet less discussed issue looms beneath: the stark lack of comprehensive data necessary to manage these scarce water resources effectively. In this two-part series on California water, we delve into the rich history of California’s water resources and management systems, unearthing the roots of our current predicament. We explore how an outdated infrastructure, designed for a bygone era, exacerbates the challenges posed by limited water availability. Our journey through California’s water management saga reveals a system in dire need of modernization, not just to cope with scarcity but to adapt intelligently to our ever-changing environmental conditions.

Our Water Delivery System

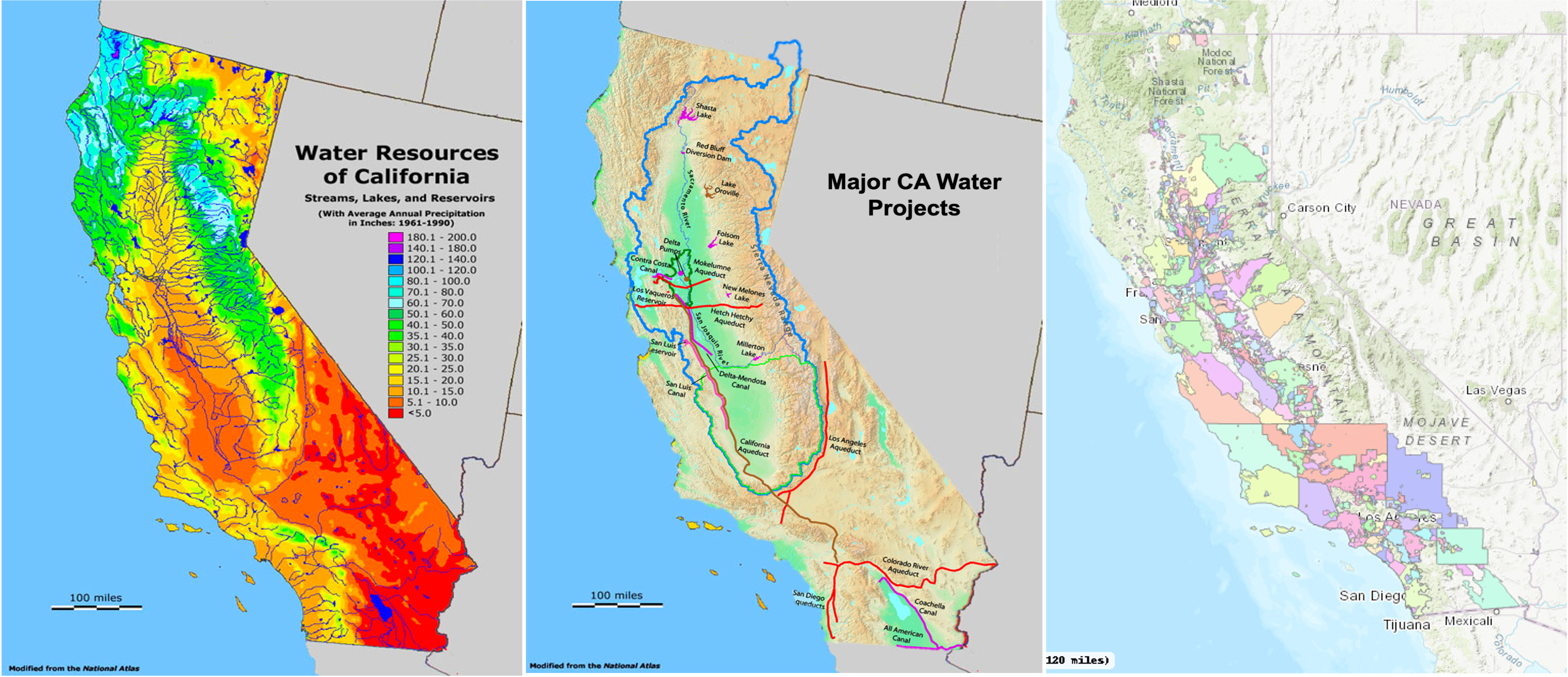

Imagine driving across the vast landscapes of California, with its iconic canals of water etching patterns across the Central Valley. These life-giving channels, often overlooked by the casual observer, are the lifeblood of the state. Our water delivery system makes it possible for millions of Californians to thrive in Southern California and empowers us to cultivate nearly 9 million acres of agricultural land (Figure 1). Yet, beneath this wonder of engineering lies a web of challenges, intricacies, and an urgent need for adaptation to meet changing climatic conditions.

Water resources in California are not distributed equally across the state. The state receives 75% of its water through precipitation in the northern part of the state, and yet 80% of the water demand occurs in the central and southern parts of the state (DWR 2023). To address this inequity, the State has developed a massive water delivery infrastructure to move water from north to south, making California the most hydrologically engineered place on earth (Figure 2). Much of the design for these vast engineering projects originated almost 150 years ago.

While the bulk of these engineering projects came to fruition in the 1900s, their inception can be traced back to the late 1800s following the passage of the Wright Act in 1887. Although there has been incremental upgrades to the water delivery system, some of the projects in late 1800s and early 1900s became the foundation of our water delivery system today (Figure 3).

Exceptional Drought – the New California Normal

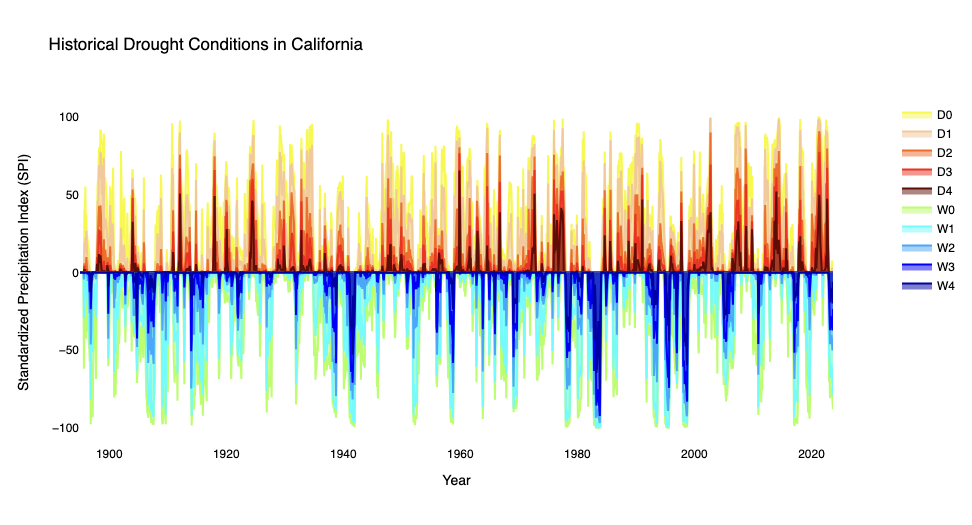

Drought periods are not a recent phenomenon for the state. California, characterized by its dry Mediterranean climate, has historically grappled with cyclic oscillations between wet and dry periods. See Figure 4 for a look at the past century’s shifts between wet and dry periods.

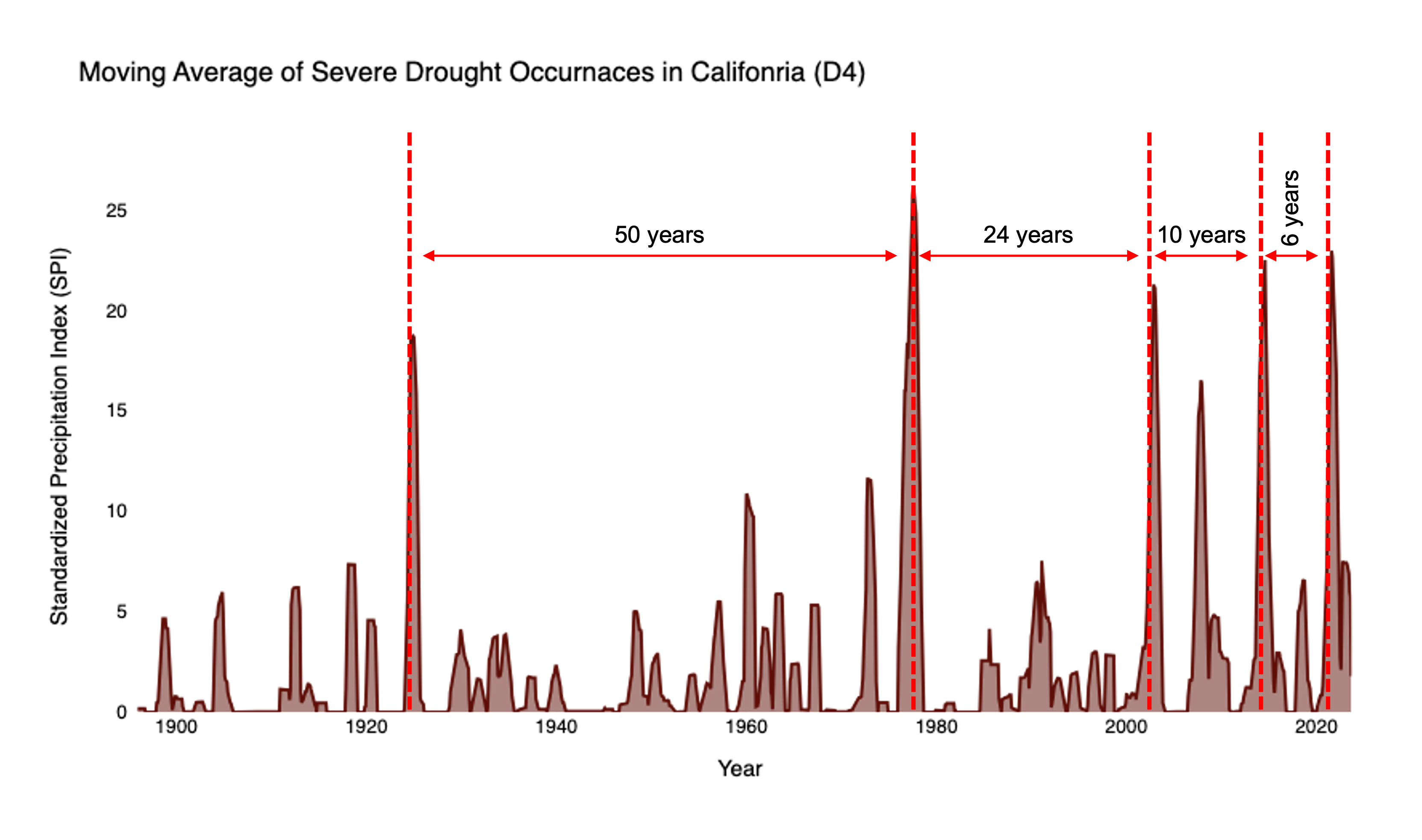

While California’s historical climate narrative is one of the stark contrasts—long stretches of drought punctuated by periods of rainfall—recent patterns reveal a troubling escalation in the occurrence of ‘Exceptional Droughts’ (Figure 5). The intervals between these exceptional droughts have narrowed dramatically. Whereas these droughts were once a rarity, occurring roughly every half-century in the early to mid-1900s, they have since become alarmingly more routine. In the post-2010 era, we are facing such conditions about every 6 years.

We are also seeing rapid changes in the Sierra Nevada snowpack and snow melt runoff. Historically, this snowpack has been a reliable source of water for California throughout the year, but it is now melting faster than ever before. Our water delivery system, designed for a steadier, more predictable rate of runoff, is outpaced by these shifts, leaving us unprepared for the accelerating changes brought on by our changing climate.

Evolution of Irrigation Practices

Not only have our sources of water (precipitation and snowpack) changed, but the way we use water has also evolved dramatically over the past 100 years. California has witnessed substantial growth in its irrigated agriculture acreage over the past century. Farmers have transitioned to growing high-value, specialty crops such as almonds, pistachios, and walnuts (Figure 6) (CDFA 2022). These high-value crops are irrigated with precision irrigation systems and need reliable and on-demand sources of water.

An Outdated Water Delivery Infrastructure

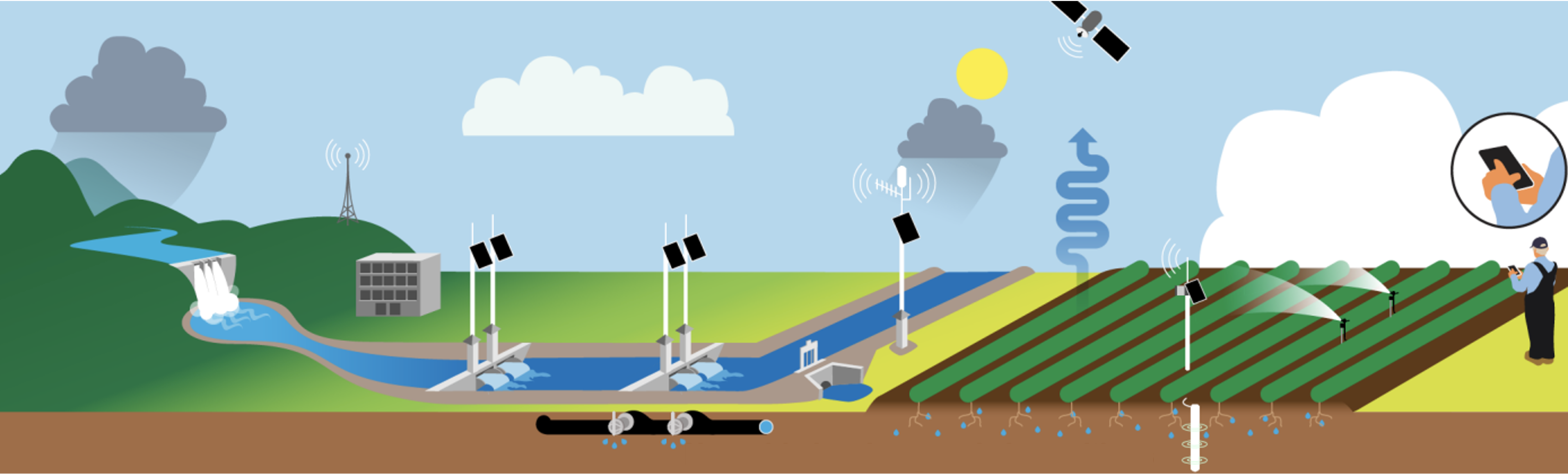

Despite the remarkable transformations of the past century, our water delivery and management system is lagging. This system is a complex network that begins at a water source, such as a river or reservoir and extends across a series of canals, pipes, and gates, culminating at turnouts that distribute the water to individual farms (as illustrated in Figure 7). These turnouts are the critical junctures where large-scale water agency infrastructure meets the on-farm irrigation systems.

The effectiveness of this delivery hinges on the system’s ability to minimize losses, adapt to fluctuating water availability, and meet the on-demand (or near on-demand) needs of current precision irrigation systems. These challenges are compounded by outdated infrastructure and operations and the growing demands of modern agriculture.

California’s water delivery system faces significant challenges, including reduced water availability due to frequent droughts and unpredictable snowpack. The system’s outdated infrastructure, characterized by gravity-fed canals, manual operations, and insufficient real-time monitoring, lacks the flexibility needed for timely water delivery. Furthermore, reliance on rigid, pre-arranged distribution schedules often leads to mismatches between water supply and demand, underscoring the critical need for modernization in the state’s water management practices.

Consequences of an Outdated System

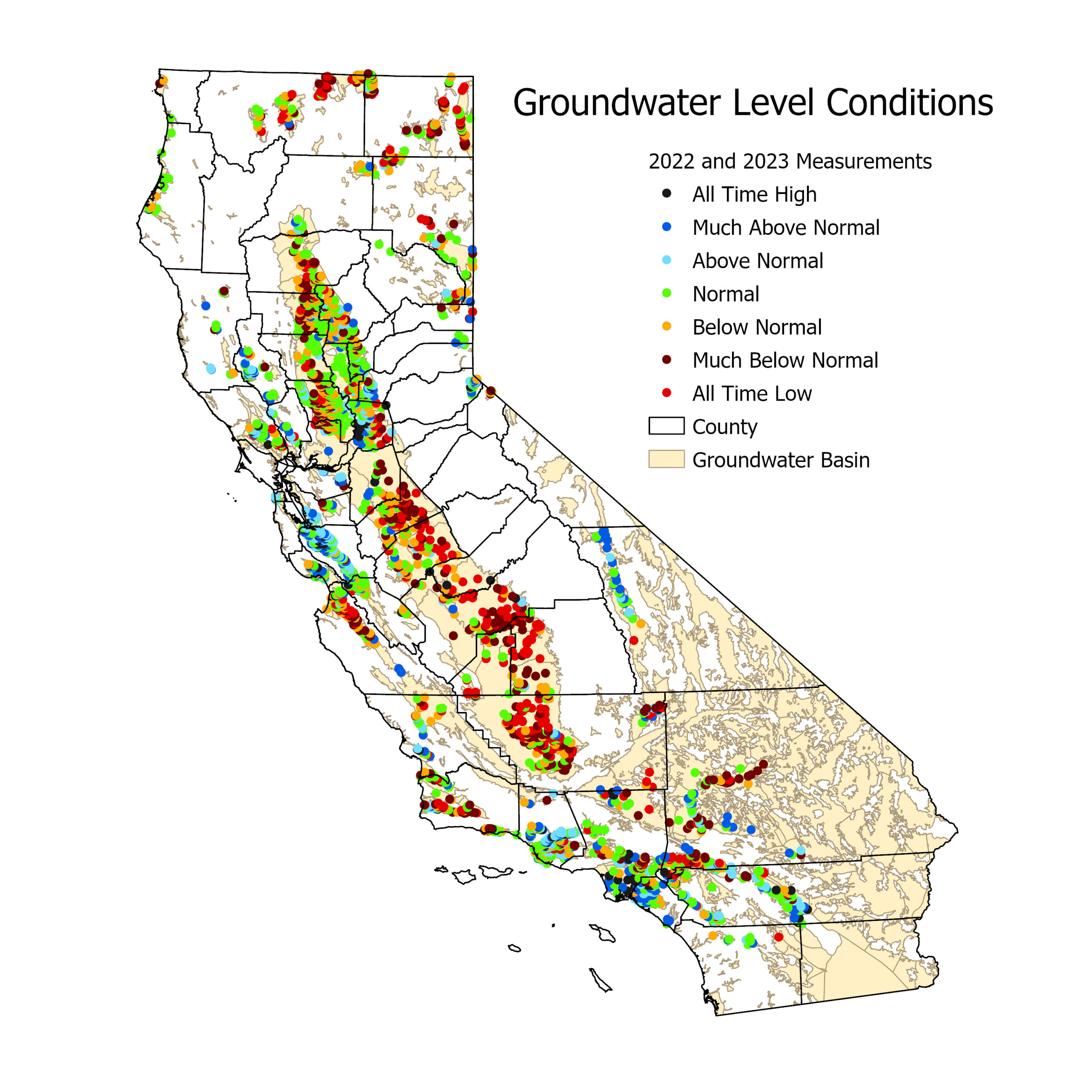

Our outdated water delivery system have serious repercussions. Our inefficient use of surface water has led to pumping more groundwater because it is viewed as an on-demand source of water. The continued over-extraction of groundwater from depleting aquifers triggers a cascade of issues, including subsidence, degradation of water quality, and lack of access to groundwater in disadvantaged communities due to the falling water table (Figure 8). To address these critical issues, California enacted the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in 2014. Despite SGMA’s long-term goals, the pressing need for immediate measures to alleviate the current strain on water resources and communities remains.

Furthermore, groundwater pumping is energy-intensive. As water tables drop, more energy is required to pump water from deeper depths, leading to heightened energy costs and increased greenhouse gas emissions. This trend perpetuates an unsustainable feedback loop: as farms rely more on groundwater, they further strain an already fragile system, exacerbating the existing problems.

The consequences of our outdated water delivery system extend beyond groundwater over-extraction—we also observe economic losses for the state, dissatisfaction among growers, and strenuous working conditions for the ditch tenders who have to drive long distances each day to troubleshoot operations.

We find ourselves at a pivotal juncture where the legacy of a century-old infrastructure is pitted against the urgency of modern challenges. It’s clear: to maintain California’s agricultural prowess, we need to modernize its water delivery system. Doing so requires addressing not just the aging infrastructure and its operation, but also the systemic challenges that impede flexibility and efficient resource management.

Water [Data] Scarcity

To date, we have relied heavily on qualitative insights—stories, descriptions, and expert interviews—to research water delivery modernization opportunities in California. The quantitative data that is necessary to complete a statewide analysis is lacking. We cannot effectively manage, much less modernize, a system when the data that should inform our path forward is non-existent. This data gap is a significant barrier that has long impeded the evolution of our water infrastructure.

In our next blog post, ‘Water [Data] Scarcity’ we will dive deeper into the impact of this data void, exploring the historical precedents that have brought us to a point where vital information is either uncollected or undisclosed. It’s time to bring water management into the 21st century and leverage the power of big data. Stay tuned for more!

At Klimate Consulting, we understand the intricacies of water resources management, agricultural sustainability, and the broader implications for our food system. We provide research-based insights and strategic guidance to organizations aiming to navigate the complexities of sustainability. To learn more about how we can help you achieve your organizational goals, get in touch or book a free consultation with us.